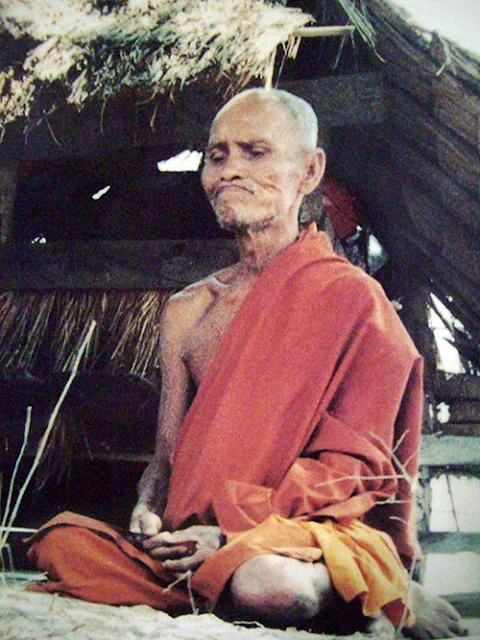

In Thai lore there is a wandering ascetic people call the “Living Jigong” — Luang Phor Suang (also written Luang Phor Sorn). He comes and goes like weather on the plains, and time seems to have lost its grip on him. Families swear three generations have seen the same lean, luminous figure: a grandfather in his nineties, a father into his eighties, and now the grandchildren — two centuries of memory pointing to one monk whose face barely changes.

Elders say he speaks fluent Khmer and may have roots in Cambodia. Though he wears a monk’s robe, he rarely stays in temples. He prefers the field huts raised for farmers in the rice paddies, staying a few days or a few months, then vanishing. Sometimes he looks every inch the orthodox monk; other times, with his long hair and unbound manner, he looks like a forest thaumaturge. In the North and Northeast he is treated as a rescuer — a living Bodhisattva. When trouble bites, people kneel, palms together, and ask him for a way through.

When followers asked his name and age, he smiled: “I forgot my name long ago, and my years as well. I’ve lived long enough — perhaps it’s time to go home.” Asked which temple he stayed in, he said: “The sky is my blanket, the earth is my bed; the whole universe is my home.” If a new shop is blessed by him at opening, owners call it immense good fortune — Thais hold monk blessings dear, and his presence feels like a hinge that turns luck.

His habits are as strange as his comings and goings. On cool evenings he warms himself with a small straw fire. If someone offers robes or money at that moment, he sometimes tosses the offering straight into the flames. Once people understood, they stopped bringing things. Some say it’s a sign of fire kasina practice — matter “transforms” in fire and takes effect elsewhere. Others say it’s his plain teaching on non-attachment. Either reading fits the man.

English accounts keep the same storyline the villages tell: a monk who appears across decades in the same districts, who gives a cup of blessed water or a single quiet sentence that somehow changes the course of a day. He never built a school of disciples, never wrote a treatise. What remains is the chorus of plain testimonies: he chanted for a new shop and business steadied; he prayed over water and a fever eased; he nodded once, and a frightened mind found its path. People say, with a certain relief, he does not live in a temple — he lives where people need him.

在泰國民間口述裡,有一位被稱為「活濟公」的奇僧——龍婆爽(Luang Phor Suang/Sorn)。他像風般來去,歲月在他身上失了刻度:祖父輩見過他,父輩也見過他,到孫輩仍碰見那個清瘦、安定的身影,容貌幾乎不改。三代記憶接力起來,便有了「三百歲、甚至五百歲」的傳說。

老人們說他講得一口高棉語,或許出身柬埔寨。雖披僧衣,卻少住寺院,最常借宿稻田間的小木寮:或數日,或數月;一現身便又杳然。時而像規矩僧人,時而披散長髮、近乎術士。於泰北、東北,他被視作救苦救難的活菩薩——逢大難,合十頂禮,心裡就像被點了一盞燈。

問其姓名年歲,他輕笑答:「名字早忘了,年紀也記不得。似乎活了很久,是時候回老家了。」問他住哪座寺,他說:「以天為被,以地為席;整個宇宙,就是我的家。」若有新店開張能請到他來誦經灑淨,店家視為大福——泰國人極重視僧侶加持,而他的出現總像轉運的關鍵。

他常以稻草生火取暖;若信眾此時奉上衣物錢財,他有時隨手擲入火堆,當場化灰。眾人明白後便不再以物供養。有人說這是火屬性修法的外顯,物在火中「轉化」,於他處起妙用;也有人認為只是他對財物不執的直白示教。無論哪種讀法,都恰與其人相合。

關於他的中文與英語敘事,其核心並無二致:數十年如一日在村鎮之間現身,遞上一杯加持水,或只說一句提醒,卻能改變一天的走向。他不立宗風、不收廣傳的弟子,留下的是無數樸素的見證:新鋪得他誦經,生意漸順;病人飲其水,病勢轉緩;遇險之人向他頂禮,心中忽然有了路。人們因此說:他不住在寺裡,他住在眾生需要的地方。