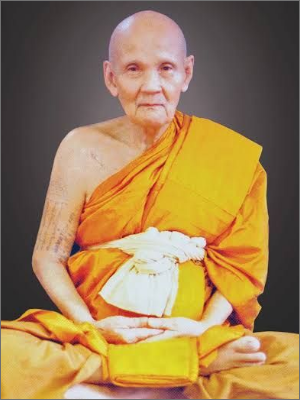

Biography of Luang Pu Du Phrompanyo (Phra Thammasinghaburacharn)

Wat Sakae, Ayutthaya • Nusri family • Born 29 Apr 1904 (B.E. 2447) — Passed 17 Jan 1990

He came into the world on a Visakha Puja Friday — 29 April 1904 (B.E. 2447) — at Ban Sam Khao, Khao Mao, Uthai District, Ayutthaya. The youngest of three to Mr. Phut and Mrs. Pueng of the Nusri family, he was named simply Du. People still tell the story of the infant who rolled off a cushion into floodwater and did not sink; the family dog barked until his mother found him floating. “A fortunate child,” she decided — not as a boast, but as a vow to raise him well.

Orphaned early, he grew under the care of his grandmother and elder sister Sum. Temples became his first schools — Wat Klang Khlong Srabue, Wat Pradu Songtham (then Wat Pradu Rongtham), and Wat Niwet Thammaprawat. At 21 he entered the robe: 10 May 1925 (B.E. 2468) at Wat Sakae. The preceptor was Luang Phor Klan (Abbot, Wat Phrayatikararam); the Kammavācācariya Luang Phor Dae (Abbot, Wat Sakae); the Anusavanācariya Luang Phor Chai of Wat Klang Khlong Srabue. Scripture, discipline, and meditation formed the braid of his days; he deepened practice with LP Klan and the famed meditator LP Pao, and sought teachings across Suphan Buri and Saraburi.

In his third rains he took to pilgrimage — Saraburi’s holy footprints, then Sing Buri, Suphan Buri, Kanchanaburi — three months of road and reflection. By 1947 (B.E. 2490) he declined outside invitations and centered his work at Wat Sakae: meditation first, service close behind.

One night before the Buddhist centennial year, as the candles thinned and the chants settled, he received a vision: three bright stars crossed the mind’s sky and he swallowed them. Startled at first, he sat with the meaning until it clarified — the Three Jewels, not outside but within. From then on his method was simple and exacting: place Buddha–Dhamma–Sangha at the heart of every breath.

His teaching cut through excuses. A heavy drinker once protested he could not meditate. “Then drink,” the master said, “but sit five minutes a day.” The man obeyed the easiest part; the habit loosened itself; in time he left the bottle and took the robe. To a fisherman afraid to accept the precepts, he said: “You might die before you cast your net. Take the precepts now. Breaking them later is still not the same as never taking them at all.”

On amulets he was precise: they help the mind if the mind is willing. “The most sacred thing is karma; no amulet exceeds one’s own good deeds.” Still, he allowed sacred objects as skillful means — better to cling to what reminds you of refuge than to what drags you into fear. Pieces blessed at Wat Sakae became aids to sati and generosity: protection and prosperity as by-products of practice, not replacements for it.

In the late years, with a heart-valve ailment and a body that asked for mercy, he kept to the hall and the rhythm of instruction. In 1989 he spoke often of parting. On 16 January 1990 he greeted a last visitor with an unguarded brightness: “From now on, I will be free from pain.” That night he told his disciples, “Whatever happens, do not abandon your practice.” At 5 a.m., 17 January 1990, he passed — age 85, after 65 rains in the robe. The hall was quiet, but the method remained: keep doing it.